Lecture Notes

MATH 125

Table of contents

Across the course, I had a lot of questions about generalizations and expansions to course content. The professor, Ricky Liu, took up the time to write awesome and super interesting answers to each. They are republished here.

Q: Is there such a thing as an infinitely discontinuous function? When I search for it, I see results for infinite discontinuities but not functions that are discontinuous in the sense that for all in the real domain. I’m curious if the uncountably infinite nature of the reals makes this sort of function impossible. If that is so, then is it possible considering only a function defined for the ‘rational domain’?

A: Yes, a function can be “nowhere continuous” (or “everywhere discontinuous”). The standard example is the function such that if is rational and if is irrational. Since every real number has both rational and irrational numbers arbitrarily close to it, is not continuous anywhere. Of course, such pathological functions usually don’t arise naturally except in real analysis courses.

Q: I was just wondering out of curiosity if there was such a thing as a ‘noninteger’ derivative, like a ‘1.5 derivative’ or a ‘pi derivative’ (beyond the integer first derivative, second derivative, etc.). I don’t know how to conceptualize it but I get the feeling mathematicians like to generalize/interpolate and that someone has come up with a definition/formalization for noninteger derivatives.

A: This is a concept that has been studied by mathematicians under the name “fractional derivatives,” though it would likely only be taught in a graduate-level analysis course. For polynomials, you can define fractional derivatives in terms of the gamma function, which is a continuous version of the factorial function defined in terms of a convergent improper integral. For other functions, there may not be a single good way to define fractional derivatives, so different definitions are used that have different properties. For more information, see the Wikipedia page for fractional calculus.

Q: The integral of a function is , were . When , the integral is . However, when one plots out the graph of as gets very close to , the shape of the graph doesn’t ‘approach’ or look anything like as even though at the integral is . It’s like there is this continuous function morphing for all values of , except at this point it is . This discontinuity is a bit jarring for me. I understand from a technical perspective that and so , but in the scope of generalizing to the family it seems a bit out of place. Is there an intuitive explanation or solace that can be provided here?

A: You have chosen your antiderivative of to be since it passes through the origin for , but actually this is not a very natural choice for since there is a discontinuity at . Instead, you should take the antiderivative that passes through the point where there are no continuity isseus for any . This gives

which satisfies

Q: I was intrigued by the arc length lecture and was requesting Wolfram Alpha to compute some interesting arc lengths. Particularly, I am interested in the function , which has an infinitely oscillating pattern as . There is expectedly no finite arclength of the function across . I tried the modified function , with hopes that for there would be a diminishing effect. However, the result still does not converge. I tried , which yields no solution - but does yield a solution, about 2.848673. I assume that there is some value in where there is some discrete jump between being computable and not being computable. I am wondering - firstly, is the significance here between computability and uncomputability mainly determined by Wolfram Alpha and not ‘pure math’ (maybe something to do with precision/computer representation)? Secondly, I am wondering how to understand and think about these discrete jumps (if they exist) in a world that I am so familiar to thinking of as continuous.

A: This is a limitation of WolframAlpha: the curve from has finite arc length for . (I will restrict to positive xx just to avoid any issues with taking fractional powers of negative numbers, which usually requires complex numbers.) To see this, we compute its derivative as

This has absolute value at most

(where .) IN particular, we can then bound the arc length by

for some constants and . One can then show by direct computation that this integral converges whenever , which holds for . A similar argument shows that the arc length is infinite for . Likely the reason WolframAlpha has trouble computing these arc lengths in cases when they are finite is that it is using an approximation method whose speed of convergence is dependent on how “wiggly” the function being integrated is. For small , its approximation method probably does not converge fast enough to give a satisfactory answer in the time allotted for the computation. In general, issues of convergence and divergence can be very subtle. We will not touch upon it much in this course, but Math 126 does cover some of these issues in the form of sequences and series.

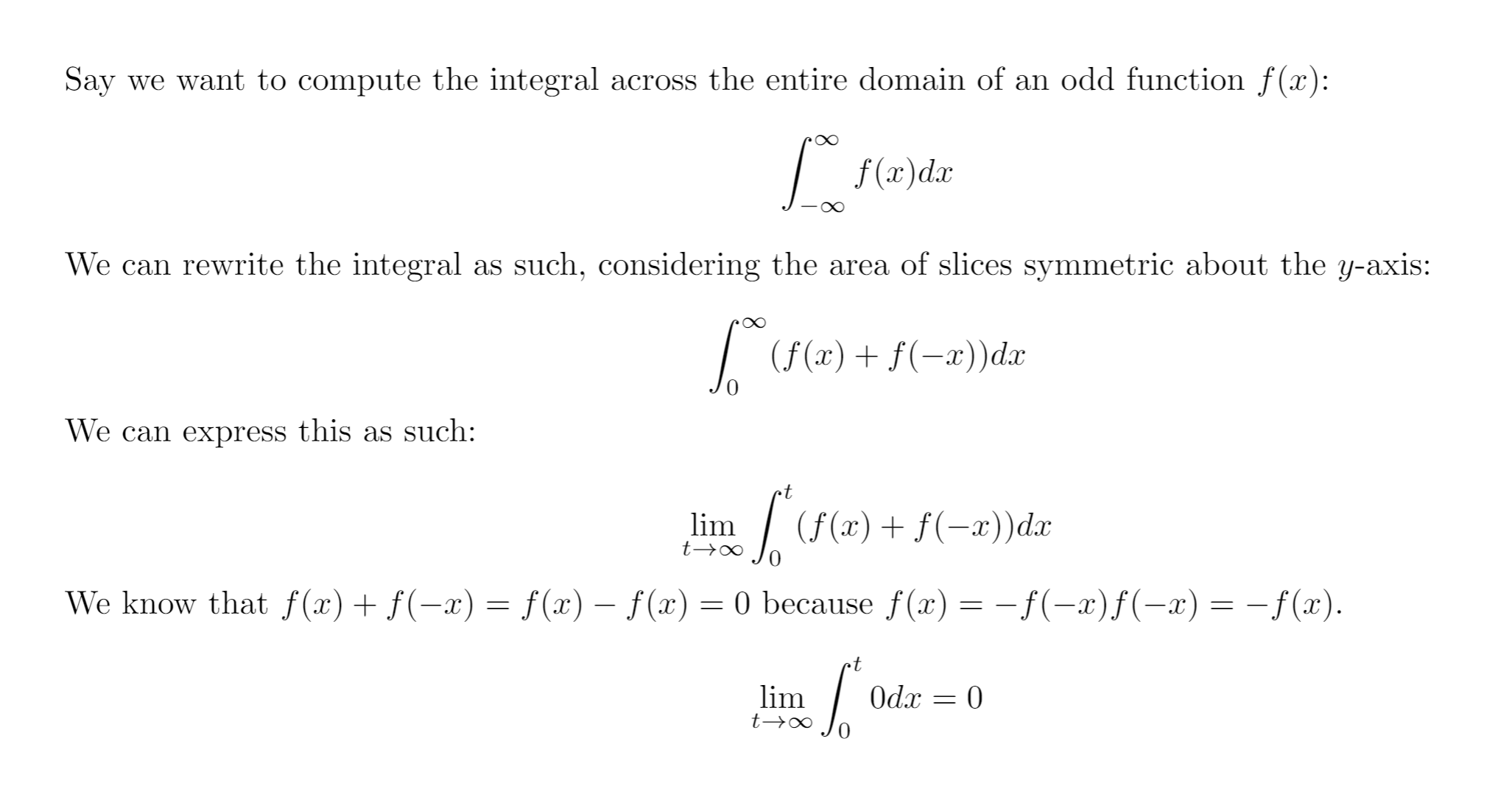

Q: What is wrong with the following argument?

A: This is a great question! Technically, the reason this argumen tis not valid is because you are not allowed to write

if the integrals on the left do not converge. (If the frist one goes to while the second goes to , you can’t cancel those out but get something indeterminate.)

Philosophically, the reason the argument doesn’t work is because you are trying to compute the infinite integral as

but you should actually be thinking of it as

\[\lim_{s\to -\infty}_{t\to\infty} \int_s^t f(x) dx\]That is, the two end points should be allowed to go to independently. It is done this way because we want to be a good approximation for for any sufficienlty large interval , not just the ones of the form that happen to be symmetric about 0.